The Master

Directed by Paul Thomas Anderson

Released in 2012

“I’m finished” are the final words of director Paul Thomas Anderson’s last picture, There Will Be Blood. It is not a spoiler, for those of you who have yet to see it, because the line drops almost as a non-sequitur when preceded by the momentous climax. Those two words grant a sense of closure to a great, ambitious film — one with an epic yet straightforward narrative. Anderson’s newest work, The Master, has no such neat ends. It is a mammoth: towering and gorgeous, yet uncanny in its thin disconnect from reality. It is a vexing character study that churns over themes of freewill, sexuality and the self. Upon viewing its opening shot of crystal blue water foaming in a WWII battleship’s wake, I thought of Tarkovsky’s 1972 sci-fi classic Solaris and its brewing ocean planet. The Master is a puzzle for those who love capital-f Film.

Known shorthand as the “L. Ron Hubbard Movie,” The Master does indeed base its title character, Lancaster Dodd (Philip Seymour Hoffman), off of the Scientology founder and blasts the groupthink of such a cult. The verbal fireworks between Dodd and a dissenter (Christopher Evan Welch) during Dodd’s introspective “processing” (called “auditing” in Scientology) of an elderly woman make those intentions clear — not to mention quite entertaining. But Anderson aims higher than just criticizing some religion or cult. He asks questions that we all dodge: Are we a product of nature or nurture? Do those around us naturally create us? We could be so much more, couldn’t we? “The master” of the title translates to at least three meanings: 1) one with a preeminent grasp on a subject, 2) one who controls another through orders and 3) one who controls another without orders.

Lancaster Dodd is “The Master,” beloved by those who follow his spiritual guidance within his Scientology-like belief system, The Cause, and exalted above all others by Freddie Quell (Joaquin Phoenix), who Dodd calls his “guinea pig and protégé.” Quell drifts across the world after the Pacific Theater of World War II left him erratic, violent and depraved. He furiously gropes a woman carved out of sand on the beach and only sees genitalia when subjected to a Rorschach test. It is no surprise that he boozes to cope with his torment; a little unexpected, however, is his homemade brand of moonshine, mixed with gasoline and paint thinner. Quell accidentally incapacitates — maybe kills — an old man with the concoction and escapes by squatting on a ship bound for New York City. The ship belongs to Dodd, who sees potential — for what is the question — in this malleable, broken soul. He also enjoys Quell’s poison and a two-way relationship between them grows.

The chemistry between Phoenix and Hoffman spells future Oscars (Lead and Supporting, respectively, I think) and, more importantly, keeps the balance of power between the two characters in constant flux. Dodd and his wife, Peggy (Amy Adams), make a mission of healing Quell back to proper mental health through their inquisitive methods. As tempting it is to label Dodd a snake oil merchant and nothing more, the film steps back to study the results of repeating simple questions (“What is your name?”) and sense-based exercises (describing the feeling, the essenceof a wall compared to a window) on Quell. The Cause treatment really has no effect, medically at least, but the final verdict remains inconclusive. The film seems to honor The Cause as much as Quell, an awe that never seems to wane.

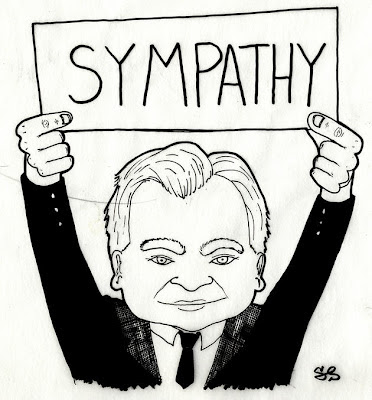

For all of Hoffman’s softly lit close-ups and monologues, however, the screen belongs to Joaquin Phoenix. Quell’s flared nostrils, squinted eyes, scarred lip and hands on his hips betray a damaged man always on the offensive — what else did war teach him? As his tantrums subside along with his reliance on Dodd, he takes back the wheel of his own life, though we are not sure if that makes him better off. His powerful kinship with Dodd (possibly sexual, but what does that really matter?) brought a sense of purpose to his life. They both saw their true selves in each other, but what purpose does truth serve for a charlatan like Lancaster Dodd? With Hoffman’s gravitas, you would think truth means everything. It is impressive that the performances are this incredible, considering Anderson’s work bears the signature of a perfectionist. Think back to auteurs like Kubrick, Malick and Hitchcock, who often stifle their acting talent with endless nuances and demands. Here, Anderson constructs an exacting cinematic construction that expresses its meaning through acting as well as direction.

The Master is unlike any film I have ever seen. Some of its power comes from what we do see, in all its rich 70mm cinematography, tailored by Mihai Malaimare Jr. The rest is in what we feel. Anderson often navigates the temporal space of his sets from a distance — The Shining’s long hallways come to mind. This technique, along with the film’s slow-paced editing and character-driven narrative, allows for our eyes to wander and pick up on the details of the mise-en-scene. The score by Radiohead’s Jonny Greenwood (he also composed for There Will Be Blood) does not underline plot points or memorable lines but just slips under your skin along with every other element. Surreal fantasies creep in without warning, and the power of The Cause starts to seem plausible.

I am curious as to how history will judge this film. There is a chance, upon closer analysis, that the academic verdict of The Master will deem it symbolically empty and hopelessly vague. I believe my first viewing offered enough validation of its merits, and what we have here will rise to a Great film. As the credits rolled, I could not escape associations with Ingmar Bergman’s Persona. That film, too, studied two individuals, one mentally ill and the other trying to heal through empathy. It is questionable whether these intimate examinations ever cured these characters, but as any film, literature or art major knows, they are how we convert our confusion into reverence.

Final Verdict:

4.5 Stars Out of 5

This article was originally written for The Cornell Daily Sun and can be viewed at its original location via this link.