|

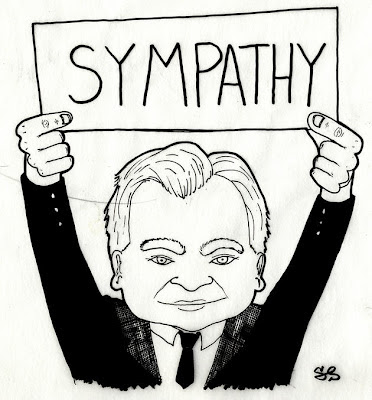

| Courtesy of Santi Slade |

“I don’t think you go to a play to forget, or to a movie to be distracted. I think life generally is a distraction and that going to a movie is a way to get back, not go away.”

That is a quote from actor Tom Noonan, who courageous moviegoers will remember as the mysterious doppelganger in Charlie Kaufman’s Synecdoche, New York. He expresses a sentiment so clear and true that I wonder why I did not assemble those exact words in that exact order by myself. Personal failings notwithstanding, the idea that we watch film to connect within ourselves rather than merely ‘escape’ via fleeting distractions fits with my fondest memories of the medium. So, why have movies been so distracting lately?

Tired platitudes blame directors Michael Bay (Transformers), Roland Emmerich (2012) or actor Nicolas Cage, who has about trademarked a style of acting/shouting in eternal meltdown. While I will personally defend Cage’s talents against his detractors, right now I charge a filmmaker who I also hold in high regard: Christopher Nolan. Our greatest living director; the man who turned superhero movies serious; the legend who dreamed of Inception? Oh, yes.

It would be borderline libel to denounce Nolan as ‘talentless,’ a ‘hack’ or a ‘talentless hack.’ He is a crafty director who challenges the audience’s expectations of linear storytelling and soundstage action scenes — see Memento for the former and Inception’s jaw-dropping revolving hallway sequence for the latter. I am quite a fan of those works, as well as ofInsomnia and the modern classic The Dark Knight. As Larry David would say, he’s “pretty, pretty … prettay good!” But there is a signature touch of his that represents a nagging trend in filmmaking of recent years, and that is his crippling obsession with minutiae, both in plot and style.

Wes Anderson (Moonrise Kingdom) rolls some eyes with his painstakingly crafted, colored and positioned props and sets. Stanley Kubrick (The Shining) drove his producers and actors mad as a notorious perfectionist. Yet the films of these two directors utilize their creator’s obsession as either a background detail or an essential key in unlocking their themes and secrets. For Nolan, he seems to be afraid of letting images speak for themselves. To secure audience comprehension, he adds flourishes that feel extraneous, like an auteur struggling to leave his mark and thus tacking on a Post-It note.

In The Dark Knight Rises, which collects the worst of Nolan’s tendencies, we are introduced to Bruce Wayne after eight years of isolation with a tabloid’s worth of gossip. At a party on the grounds of Wayne Manor, the Gotham City Mayor notes Wayne’s absence, policemen remark how Wayne has not been seen for years, maids chatter about how “disfigured” the unseen Wayne has become and adversary John Daggett jokes that Wayne is some Howard Hughes-esque recluse, “peeing into Mason jars.” This repetitive exposition is an example of ‘tell’ over ‘show,’ where we do not feel a grain of the solitude Wayne suffered but simply hear how bad it must have been from (mostly) unknown talking heads. Nolan loves to parallel cut between several proximate locations in order to string together a bustling setting, but he forfeits any moments of silence or contemplation in his depiction (see film theorist David Bordwell’s recent essay, “Nolan vs. Nolan,” for an in-depth analysis of the director’s overactive editing style).

Plot is clearly Nolan’s focus and his number one goal to communicate. Why, then, do his stories end up so twisted and full of holes? Allow me to clarify: I believe plot holes are one of the weakest arguments you can impose against a movie. Plot holes may not be apparent on a cursory viewing, and thus spotting them gives a viewer the impression that they are closely analyzing the film and engaging in nuanced ‘film criticism,’ as scholars call it. However, this approach can be likened to disassembling a movie’s SparkNotes, divorcing themes, composition and intent from a film and instead studying often-irrelevant inconsistencies in a film’s universe.

Unfortunately, Nolan perpetuates this increasingly mainstream method of pseudo-analysis by tying theme and plot so strongly and, at least in the case of The Dark Knight Rises, so sloppily. To those who have seen that movie, you are aware of that already infamous plot twist at the end (accompanied by a literal twist of a knife, to jog your memory). It razes most of the film’s fiction up to that point, leaving dozens of ruinous and unfathomable assumptions in its wake. The inclusion of the twist was likely out of necessity to spice up the final act. Roger Ebert coined the phrase, “Keyser Soze syndrome,” in observation of the trend following The Usual Suspects’ release when a film drastically alters its reality in the final act. See Fight Club, The Sixth Sense and Nolan’s own Memento for the fad’s winning protégés.

Perhaps Nolan’s greatest weakness is his inability to give into the mystery of his subjects. Inception spends nearly an hour explaining the logic of dreamworlds to the viewer, along with throwing out a handful of inconsistent “dream within dreams” time scale ratios. Think how much more unpredictable and, according to both psychologists and personal experience, realistic a lack of rules would have been. The Dark Knight actually carries a soul — the silent shot of The Joker with his face out of a police car window, basking in chaos shakes your bones. But Two-Face’s circuitous speech at the climax divulges the Hollywood tendency for too much closure. And as for The Dark Knight Rises, Nolan told Rolling Stone magazine in July that it was not “political.” The plot’s prominent populist uprising — with insurgents brandishing Soviet AK-47s — precludes this notion, regardless of his stated clarification.

Saying all this, I still love much in Christopher Nolan’s work and would be lying to say I was not counting the days until his next feature. He is in the unique position to reach a sizable fraction of the world’s population, not only to entertain, but to inspire, comment and provoke. He could even doodle with an experimental film and people would see it. I want to leave his movies pondering big questions, and not just whether or not that damn spinning top fell.

This article was originally written for The Cornell Daily Sun and can be viewed at its original location via this link.

No comments:

Post a Comment